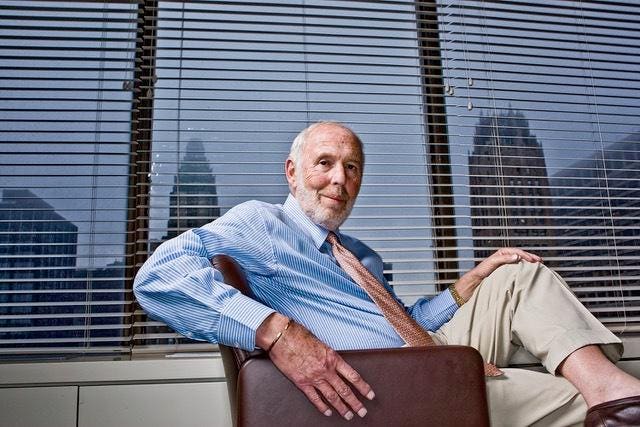

Jim Simons, a math professor turned hedge fund founder who pioneered investing with automated quantitative models and used his riches to become one of America’s leading philanthropists, died Friday at age 86 at his home in Manhattan, his foundation announced.

Simons was a mathematical genius who chaired the math department at Stony Brook University, but he left that career to try his hand at the markets in 1978, when he was 40. He founded hedge fund Renaissance Technologies in 1982 and created its Medallion Fund in 1988, famed for beating the broader market and any investor who tried to compete with it—and also for closely guarding the secrets for how it did so.

Renaissance is based in East Setauket, New York, 70 miles east of the city near the shore of the Long Island Sound. It has long valued its distance from prototypical Wall Street traders, instead hiring some of the world’s brightest mathematical minds. Its spartan website notes that 90 of its 300 employees have PhDs in math, physics, computer science or related fields.

Renaissance now manages about $50 billion in assets, and its Medallion Fund for decades has only been open to Simons and the firm’s employees. The Medallion Fund charges a 4% management fee and performance fees ranging from 36% to 44%, much higher than any other major hedge fund, but it’s been more than worth it. After fees, the fund has still generated an annualized net return of more than 30% since inception. Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway has mustered a mere 20% compounded annual gain in comparison.

That track record made Simons the 51st richest person in the world at the time of his death, with an estimated $31.4 billion fortune. He first appeared on the Forbes 400 list of richest Americans in 2004 with a net worth of $2.5 billion.

Simons was intensely private, and the specifics of the investing strategy that fueled his success remain mostly a mystery. He made his last public appearance in September 2023 at the 11th Annual Forbes 400 Summit on Philanthropy in New York. He and his wife Marilyn Simons were presented with the Forbes 400 Lifetime Achievement Award for Philanthropy and spoke about their charitable work with Forbes Editor-at-Large Maneet Ahuja. Jim credited Marilyn with being the initial driving force behind the Simons Foundation, which they founded in 1994. “I just made the money and Marilyn gave it away,” he quipped on stage.

That was likely true when they first began making charitable gifts. But in his later years Simons committed himself more personally to their charity. He stepped back from leading Renaissance in 2010, and he and Marilyn have given more than $6 billion away via their foundation, making them the sixth-most philanthropic givers in America, according to Forbes. The Simons Foundation, which had $4.9 billion in assets as of its most recently available tax filing, primarily supports education and math and science research.

“The whole economy is more and more dependent on quantitative skills, and we’re behind in teaching them,” Simons told Forbes in 2016.

Last year, the Simons pledged $500 million over seven years to Stony Brook University in the second-largest donation ever to a public college. Simons became the chair of the math department there at age 30 after stints teaching at Harvard and MIT and became renowned for his work on topology and understanding the features of complex geometric shapes. In 1976, he won the American Mathematical Society’s Oswald Veblen Prize, the highest honor in the field of geometry.

“Stony Brook means a lot to us,” Simons said at last year’s Forbes Philanthropy Summit. “The department was only so-so, but [Nelson] Rockefeller was governor and he loved the state universities, so I had all the money I needed to build up the math department, which I did.”

The school is also where he met Marilyn while she was a PhD student there, and last year he also recounted the humorous, if antiquated, story of how they were introduced.

“My ex-wife was going to Europe for the summer, so I had to take care of our three children, so the university sent someone over to see if she would do that job,” he said. “We talked and we talked and we talked, and finally I said, ‘Do you have a boyfriend?’ And she said no, and the rest is history.”

The couple has continued to invest heavily in math education, and in 2004, they founded Math for America, which provides stipends for 1,000 STEM teachers every year in New York City and has distributed more than $300 million over two decades. The foundation has given millions more to the National Museum of Mathematics, known as MoMath, in New York. In a 2017 interview with Forbes, Simons explained why helping math teachers was important to him.

“If you know enough math today to teach in high school, then you probably know enough to work for Google or Goldman Sachs or Renaissance Technologies,” he said. “They pay a whole lot more than high school teaching. So, that means that not so many people who know the subject are going to go into that field, the field of teaching.”

The Simons Foundation has also distributed hundreds of millions of dollars to support cancer and autism research at institutions like the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.

“We have a team of people at the foundation which spends $100 million a year working on autism and understanding it better,” Simons said last September. “It’s not the only thing the foundation does of course, but it’s one of the important things that it does.”

One of the foundation’s most recent initiatives was $90 million in contributions to the Simons Observatory in Chile, where the finishing touches are being put on advanced telescopes at an elevation of 17,000 feet near the summit of Cerro Toco, a volcanic mountain in the Atacama Desert. The telescopes are expected to be able to view the so-called cosmic microwave background, mapping all the radiation dating back to the Big Bang, with more detail than ever before. Simons’ intelligence and wistful curiosity shined through as he wrapped up his interview with Forbes last year, discussing the project.

“The conventional thinking is that the universe started with a point, with one point, and then hugely expanded, which is called inflation. If that’s true, that big expansion would cause gravitational waves. The first thing we’re going to do with this telescope is see, are there really primordial gravitational waves right at the beginning?” Simons said. “Personally, I kind of hope we don’t find these gravitational waves because I don’t believe the universe started with a point. I think the universe has gone on way before anything. But we’ll see.”

Read the full article here