There’s nothing like bankruptcy to provide a cautionary tale. As Benjamin Franklin said, “nothing is certain except death and taxes”—and bankruptcy, being corporate death, is remarkably common.

The most recent example comes from Fisker, an admirable upstart in the EV sector that set out to emulate Tesla with beautiful cars (yes) with decent range (yes) and make lots of money doing it (no).

The phenomenon is nothing new: one extremely successful company attracts countless imitators, most of whom disappear in what feels like a fortnight. Far from picking the next Tesla, investors often end up picking the next fiasco. Anyone who bets on a new company should realize that the odds are stacked heavily against them. For every Amazon that goes on to grab the brass ring, hundreds of other dotcoms become mere footnotes.

Long before vehicles dreamed of being electric, when the internal combustion engine was the new new thing, hundreds of automobile companies emerged to try to imitate Ford. With a dream, a prayer, and some startup cash, a staggering array of upstarts crisscrossed the United States. There was the Dort, the Caloric, and the Stout Scarab. There was even Kent’s Pacemaker, the DODO, and the Twombly. Mr. Twombly had more problems than his failed auto company: he suffered an expensive divorce and was jailed for bigamy and misconduct.

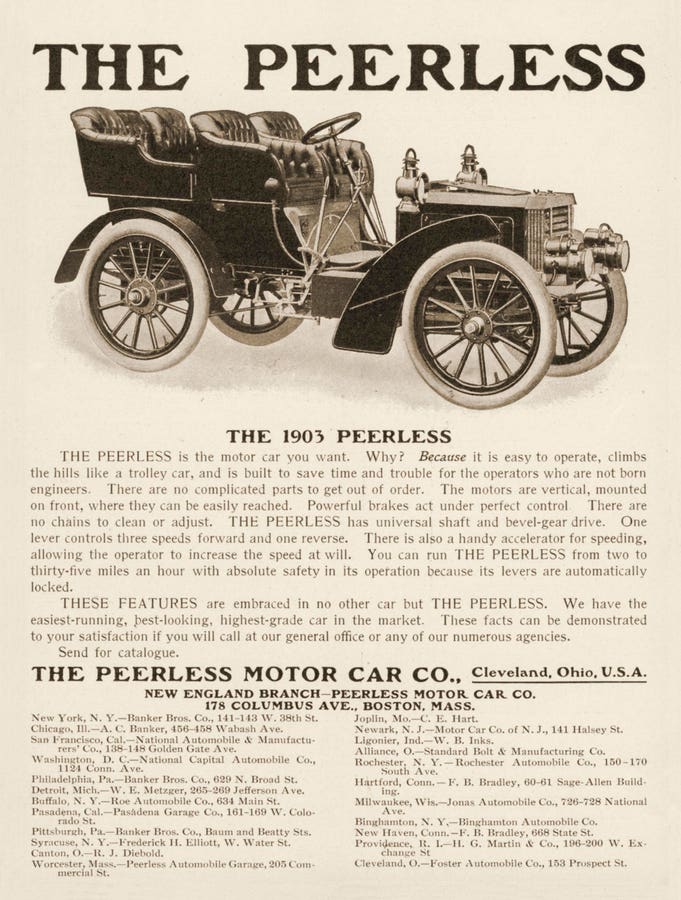

My personal favorite was Peerless Auto, which despite its motto—“All that the name implies”—was anything but. Along with Packard and Pierce-Arrow, the company established a reputation making luxury automobiles. Peerless was an innovator, and popularized vehicular features that became standard, such as drum brakes. Production started in 1900 in Cleveland with engines under license from French company De Dion-Bouton. By 1907, Peerless was famous and successful. But the Great Depression was too much for the company. Sales of luxury autos collapsed. The last Peerless was produced in 1931, and the company reinvented itself as a brewery after the end of Prohibition in 1933.

The tale of Peerless and many of its peers reminds us why Warren Buffett’s admonition to buy only “wonderful companies at a fair price” is so important. As Buffett explains, a wonderful company is one that has an “economic moat”: one which protects it against unbridled competition. This can be a strong brand, a high barrier to entry, a patent, or high switching costs. What it can’t be is one of many entrants in a faddish race to the bottom. Even with metrics such as return on invested capital, it’s hard to make these distinctions—which points to the importance of diversification across companies and sectors.

The next time your neighbor implores you to buy the latest disruptor, ask yourself whether the company is likely to be around in 10 years. If the free cash flows, balance sheet, and market positioning don’t offer a firm “yes,” then the answer might be to stick with a mature, boring company where business is dull and dependable. After all, the next Tesla might be the next Fisker, which might be the next Peerless, which might find itself at the mercy of all too many peers.

Read the full article here